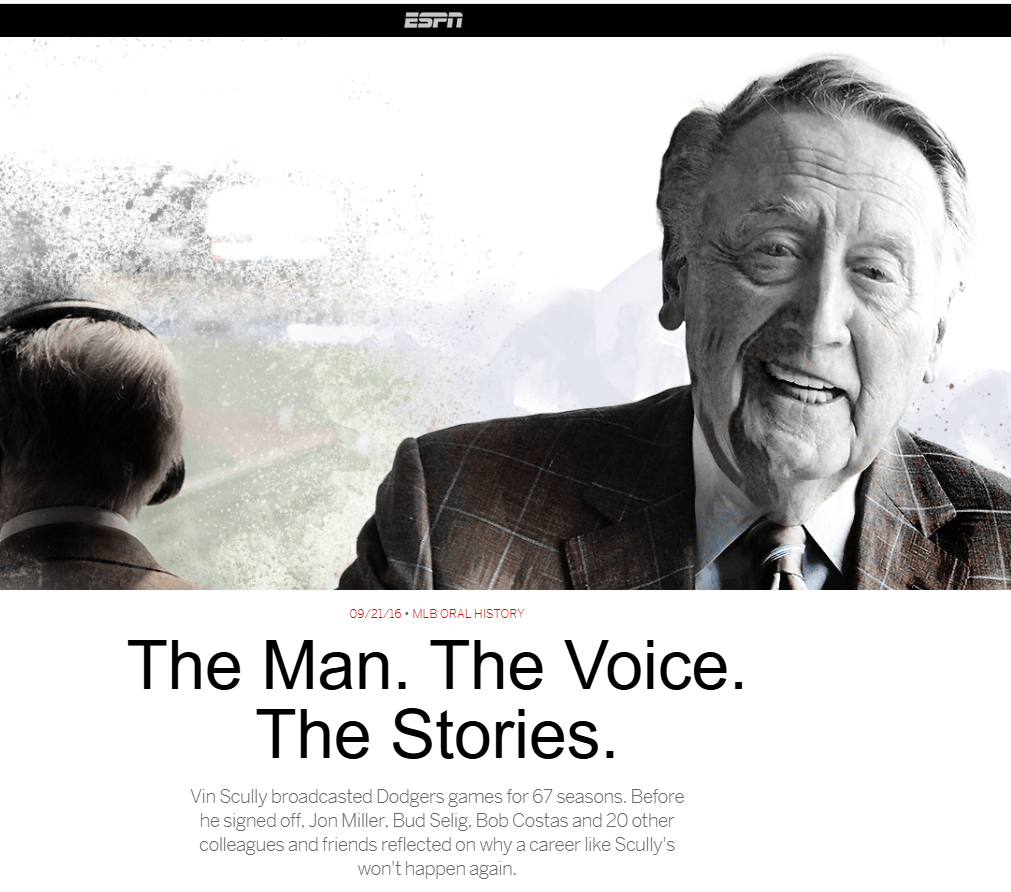

In the research for the book that could add depth and context about Vin Scully and his life, we found various published material that made it into the manuscript and other pieces that didn’t. Here we present and preserved more martial. Stories going back to the 1950s and beyond, and others posted most recently, continue top tell the Scully story (*links to the items are in the boldface in the dates):

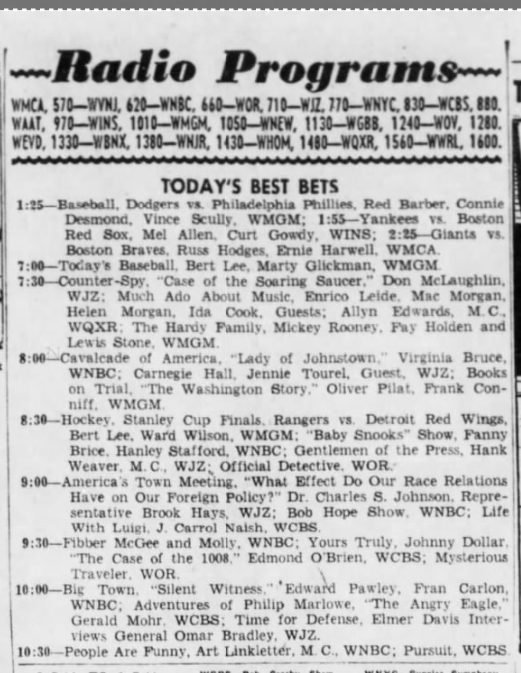

== April 18, 1950: The Brooklyn Eagle newspaper lists the first Dodgers’ broadcast for Vin Scully — calling him “Vince”:

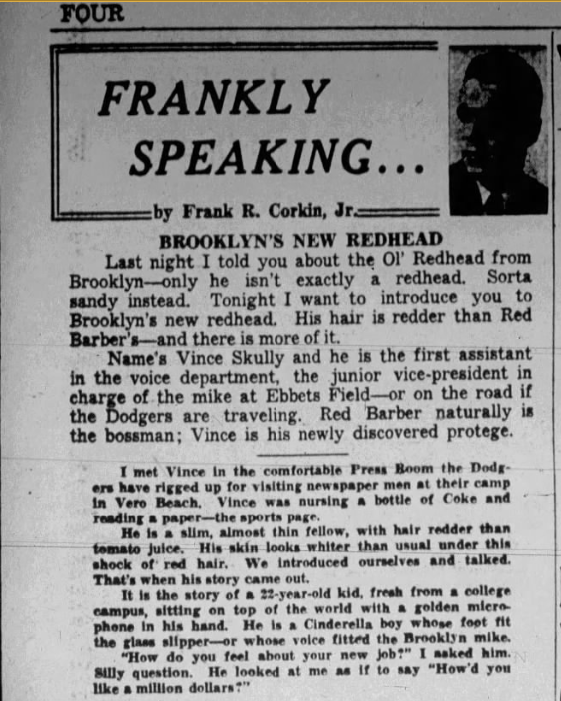

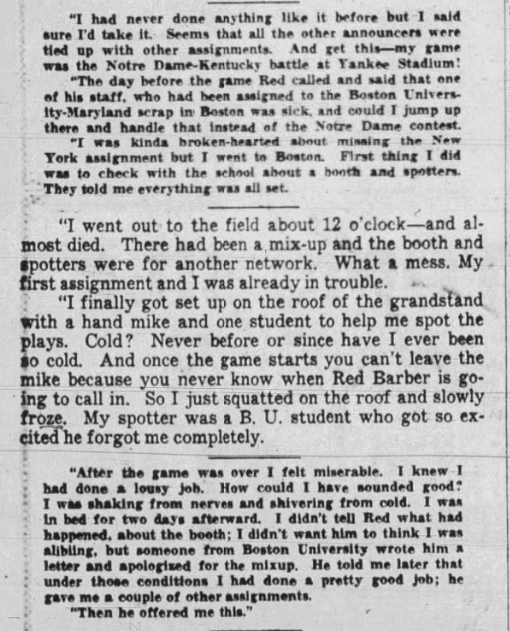

== March 24, 1950: The Journal of Meriden, Conn., ran a column by Frank Corkin that introduced readers to “Brooklyn’s New Readhead” — and then went on to misspelled his last name. It also kept with the trend of calling him “Vince” as his first name. Corkin also spelled it as “Skully” as he previewed the column with a piece about Red Barber the day before.

The misspelling seems to be corrected further into the column, but, if we are speaking frankly here, an editor could have caught the discrepancies and fixed them, right?

== Oct. 6, 1956:

Vin Scully’s call was incorporated into a national TV broadcast for the first time with the 1954 World Series involving the Brooklyn Dodgers were involved. Two years later, this kinescope captures Game 3 of the 1956 World Series is, by all accounts, the earliest clip of Scully doing a live game, according to TV historian David Schwartz. Teamed with the New York Yankees’ Mel Allen, the 28-year-old Scully would also call the last half of Don Larsen’s Game 5 perfect game two days after this, including this last-out description:

Note how in this game, right before the first-pitch, the camera turns to Scully in the press box.

He he does a live commercial for a Papermate Capri Piggyback Pen, one so far ahead of its time, it has a second ink container inside to use when the first run runs out.

== Sept. 23, 2015: Vin Scully is official recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as “The Longest Career as a Sports Broadcaster for a Single Team.”

And he had another year to go.

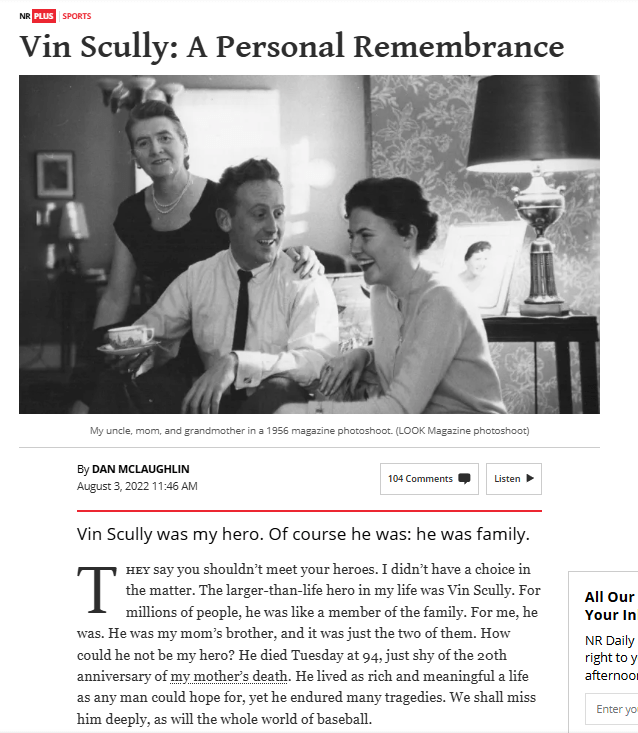

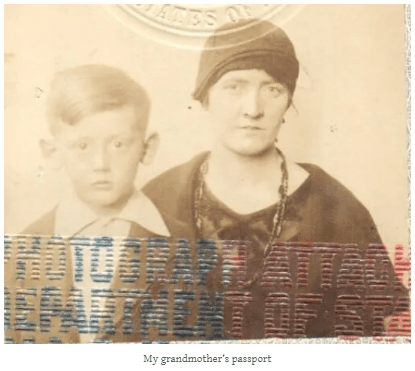

== Aug. 3, 2022: Dan McLaughlin, a Senior Writer for the National Review — and Scully’s nephew — posted a personal remembrance about his uncle’s passing that included a family find below:

He never wrote a memoir. He never needed to. Every story he had to tell that could be spoken of in public he spun on the air. He made baseball broadcasting sound like literature. Of course, I grew up a baseball fanatic, with Vin as an uncle. And a fanatic about talking about the game, studying it, and understanding it. …

As a cop’s son growing up in the New York suburbs in the 1970s, I treated a visit from Uncle Vin as something on the order of having Batman drop by the house. Any other time, we were ordinary people, but he was a Star. He got us down on the field to meet Tom Seaver and Don Sutton and the rest at my first baseball game, when I was four. We’d hang out by the front window trying to guess what color rental car he was driving. But then, we’d go to a nearby diner, because it was where my grandmother liked to go. I have a vivid memory from those years of Vin and my dad, both in shirt and tie, changing a tire in the parking lot at Hogan’s Diner. …

I do not give too much away, and likely will not surprise anyone, in saying that the private Vin was exactly the same as the public Vin. He was generous and even-tempered and in every sense a gentleman. When he called the house, he broadcasted: you could hear his voice coming out of the phone halfway across the room. In later years, a voicemail from Vin was a small treasure in itself, with a beginning, an anecdote, and a conclusion. …

At a certain point in my writing career, I decided not to mention my connection to Vin, partly so I wouldn’t be trading on his good name for attention, and partly — as I moved further into the combative arena of politics — so I wouldn’t give him any headaches. The one time he mentioned me on air, at least that I know of, was the first game back after 9/11, given that I had worked in the World Trade Center and been there that day. A few readers put two and two together, but I really only had a few readers then anyway. But eulogies are a time for sharing. …

(Note: McLaughlin wrote this piece on Sept. 13, 2001 for the National Review about being at Ground Zero on 9/11 and was writing a baseball blog called “The Baseball Crank” at the Providence Journal).

There was a great gift in growing up knowing someone who had literally talked his way from nowhere into the Hall of Fame, who had become the best at what he did. He was my hero because of who he was and how he lived his life in public and in private, but also because he represented all the American possibilities — and that you could do great things and still be good.

== July, 2024: The Society for American Baseball Research released a publication titled “Dodger Stadium: Blue Heaven On Earth,” and the focus of Chapter 13 written by Michael Green is titled ” ‘Scully’s Shrine’: A Broadcaster and His Ballpark.”

Green, who penned an essay for “Perfect Eloquence,” cites several sources in his notes about information he found for this piece. One of them was a story I did called “Scully Recalls Culture Shock of L.A. Move 50 Year Ago” for the Southern California News Group in 2008.

Other interesting resources we saw that Green used:

= June 16, 1963: Los Angeles Times media writer Don Page writes “The Radio Beat: Transistor Testimonial To Scully.”

= July 16, 1966: The Sporting News’ Dick Kaegel writes, “Even Writers Toss Bouquets at Scully.

= April 8, 1985: The Los Angeles Times’ Rick Reilly pens “Vin Scully: In 36 Years as Voice of the Dodgers, He’s Never Been at a Loss for Words.”

= May 27, 1966: The San Pedro News-Pilot’s Donald Freeman writes “Scully: Old Pro of the Dodgers.”

Green also uncovers this quip about Scully’s approach to broadcasting. Green wrote:

Scully admitted to one time when the Dodger Stadium crowd carried him into an emotional reaction he apparently never repeated. Although he said, “I am not neutral. You cannot travel with and live with and become friends with members of a team and not want them to do well,” he prided himself on his on-air objectivity.

That quote came from the annual reissue of the book, “The Complete Handbook of Baseball,” from 1975, a year after the Dodgers-Oakland World Series, and the chapter cited is “Vin Scully: How I Announce a World Series.”

Green continued his story with a reference to a piece by the Los Angeles Times’ columnist John Hall in 1970 titled “Vin or the Egg”:

On at least one occasion he had to find a way to vent his support for the Dodgers … After a Dodger delivered a key hit in a game against the Giants, “(s)uddenly, that tremendous animal roar of the crowd got to me. I felt like I was going to explode. I had to do something. I leaned out of the booth and started pounding my fist on the facade of the stadium. None of the listeners knew what I was doing, though. I’d at least pressed the cough button on the mike, the only time I ever did that. When I finally got the fist-pounding out of my system, I resumed announcing as calmly as I could. One of the letters I got later asked how in the world I could be so cool and detached during such an exciting game.”

So, what game was that? In Green’s notes at the end of his chapter, he figures it out:

“Scully’s memory was legendary and he demonstrated it here: He thought he had reacted to a key triple by outfielder Lee Walls. The only triple Walls hit with the Dodgers was (as a pinch-hitter in August, 1962) not in a crucial situation and occurred against the Philadelphia Phillies in the seventh inning, when (Jerry) Doggett would have been broadcasting. That hit did give the Dodgers a lead. But in the second game of the 1962 playoff against the Giants (on Oct. 2), the Dodgers needing to win to force a third game and starting the inning down 5-0, Walls (again as a pinch hitter) doubled in the sixth, scoring two runs and advancing to third on the throw, and giving the Dodgers a 6-5 lead.”

Green also includes links to the RetroSheet.org box scores of both games above.

Here’s more total recall of that contest for those who never saw it, read about it, or could understand how a three-game playoff series worked at that moment in baseball history:

The box score play-by-play described Walls’ double as coming with the bases loaded, clearing the bases as he took third on the throw home, thus driving in three runs. On the next play, Walls scored on a fielder’s choice off a ground ball hit by Maury Wills — and Walls injured Giants catcher Tom Haller on the play, eventually knocking Haller of the game. Also, after Walls’ hit in the sixth, the Giants brought Don Larsen to pitch in relief. The same Don Larsen just seven years removed from his 1956 World Series perfect game against Brooklyn’s Dodgers.

As for the rest of the game: It got more intense. The Dodgers’ seven-run sixth inning that allowed them to take a 7-5 lead still wasn’t enough. The Giants tied the game with two in the top of the eighth — during that rally, Willie Mays was thrown out trying to go from second to third on a run-scoring base hit. Tommy Davis, who had been playing center field, as Willie Davis was substituted out, was the one who threw Mays out. The Dodgers won in the bottom of the ninth when Ron Fairly hit a line-drive sacrifice fly to center field with the bases loaded to score Wills, who walked to start the inning. He went to second on a walk to Jim Gilliam, and was sacrificed to third on a bunt by Daryl Spencer — who pinch hit for No. 3 hitter Duke Snider for that sole purpose of bunting. Tommy Davis was walked intentionally to bring up Fairly, who subbed in earlier at first base for Wally Moon.

What a game.

The next day, the Giants scored four in the top of the ninth to eliminate the Dodgers, 6-4, and Larsen got the win in relief of Juan Marichal, having pitched to five batters in the bottom of the eight. Dodgers reliever Ed Roebuck, who came in for Johnny Podres in the sixth, was tagged for all four runs in the ninth and saw his record drop to 10-2. Roebuck left the game after taking a line drive off the bat of Mays, credited with a bases-loaded single, but Roebuck responsible for all the runners he left on as Stan Williams and Ron Perranoski tried to stop the bleeding, with Don Drysdale warming up in the bullpen. The game also saw Maury Wills, the eventual 1962 NL MVP, steal three bases, including Nos. 103 and 104 in the seventh inning, swiping second and third and then scoring on a throwing error, giving the Dodgers a 4-2 lead. That MLB record stood for several decades.

But the game before that … no wonder Vin Scully remembers it so well.

== Summer of 2024: Vin Scully’s biographic resume on BR Bullpen, the Baseball-Reference.com website of note for all statistical baseball, has included “Perfect Eloquence” as one of its reference materials for further reading.

Here are a list of the some of the other references:

= Anthony Castrovince: “Vin Scully, legendary broadcaster, dies at 94“, mlb.com, August 2, 2022.

= Ken Gurnick: “Scully’s swan song season a memorable one: Iconic broadcaster’s farewell among most captivating storylines of 2016“, mlb.com, December 29, 2016.

= Gary Kaufman: “Vin Scully: For 50 years, an Irish redhead from the Bronx has been the gold standard for baseball announcers”, Salon, October 12, 1999

= Tyler Kepner: “The Farewell Tour Comes to Vin Scully”, The New York Times, August 27, 2016.

= Austin Laymance: “New address: Dodgers now on Vin Scully Avenue: Club, city of Los Angeles formally dedicate ballpark street to legendary broadcaster“, mlb.com, April 11, 2016.

= Matt Monagan: “On Vin Scully’s 90th birthday, let’s celebrate a great moment from every one of his decades“, “Cut4”, mlb.com, November 29, 2017.

= Joe Posnanski: “Stories reveal Scully’s lasting effect on lives: Iconic announcer enshrined in Dodgers’ Ring of Honor“, mlb.com, May 3, 2017.

= Eddie Timanus: “Vin Scully, Hall of Fame broadcaster and longtime voice of the Dodgers, dies at 94″, USA Today, August 2, 2022.

Related sites:

= Koufax’s 9/9/65 perfect game, final inning: Scully’s call and its transcript

= Vin Scully at the SABR Bio Project (Greg King)

= National Baseball Hall of Fame

= Radio Hall of Fame

= Internet Movie Database

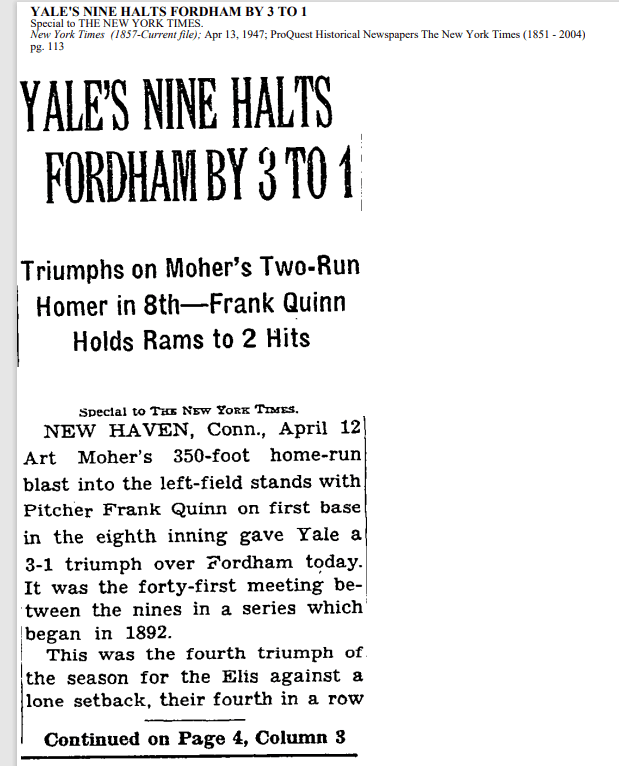

= April 13, 1947: Two days before Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Vin Scully’s Fordham team plays a game against Yale, which featured first baseman George H.W. Bush. The story and box score from the New York Times’ archive show Scully went 0-for-3 with four putouts in center field, while Bush went 0-for-4 with 10 put outs at first base.

And, in the story, “Vin Scully whiffed”:

== Jan. 25, 1950: Vin Scully’s first mention in Variety magazine. It was months before his Dodgers career began, in this letter from William A. Coleman, chairman of the AM-TV Division of Scully’s alma mater, Fordham University, is this promotion of a recent alumni as a potential announcing star of tomorrow:

== August, 2022: For the website WalterOMalley.com, Brent Shyer has a piece posted titled “Vin Scully: The Greatest Ever.”

The story by Shyer, who also did an essay for “Perfect Eloquence,” is dotted with many rarely-seen photographs of Scully, from the O’Malley archives.

Shyer’s piece ends:

And all of us – his “marching and chowder society” – thank him for his unprecedented years of service to Dodger fans and for bringing unparalleled joy and excitement to his objective broadcasts. Many fans consider Scully the greatest Dodger left-hander of all-time.

== Aug. 3, 2022: Dodgers team historian Mark Langill’s tribute to Scully upon his passing on the Dodgers MLB.com blog includes:

Another key to Scully’s success was his friendship with Jerry Doggett, his broadcasting partner for 32 seasons from 1956 to 1987. Doggett, who passed away at age 80 in 1997, was 11 years older than Scully and accepted his role as the Dodger’ No. 2 broadcaster without jealousy. Scully and Doggett played golf on the road and filmed commercials at the stadium’s Union 76 station to promote upcoming events.

“Vin is very humble and low key,” Doggett said in 1982. “He doesn’t like a public image. He’s embarrassed to be recognized in a public place. I’m sure he’s aware of his impact, but he likes to suppress it. He hasn’t changed much. He’s thoughtful, considerate, friendly. He will stop and talk to everybody. He’s outgoing and very gracious. He gets attention and gets noticed everywhere, and he handles it very well. It would drive some people crazy.”

And there is this gem of a story:

In 1952, the St. Louis Cardinals had a reserve outfielder named Larry Miggins, a former Fordham Prep classmate of Scully. In their middle school days, the pair sat in the back of an auditorium and pondered their futures. Miggins wanted to be a pro ballplayer. Scully dreamed of broadcasting baseball. Their combined fantasy went along the lines of “Wouldn’t it be something if you hit a home run in the Major League and I was behind the microphone …”

After graduation, the friends went their separate ways. Miggins went into the Merchant Marines Academy; Scully enlisted in the Navy. When Scully got the Dodger job, he read in The Sporting News about a group of St. Louis prospects, including Miggins.

The Cardinals arrived in Brooklyn in May 1952. Miggins and Scully had dinner with a group of friends. Scully looked forward to seeing Miggins at Ebbets Field, but Miggins wasn’t sure if he would play. The odds of Scully describing any Miggins at-bat were reduced because he was on the air only in the third and seventh inning as a backup to Barber and Desmond.

But Miggins stepped to the plate in third inning on May 13 against Dodger starter Preacher Roe and hit a home run. Miggins’ MLB career lasted only 43 games and he had two career home runs in 100 plate appearances. Miggins quit baseball in July 1954 and embarked on a 25-year career with the United States Parole and Probation Department.

“A miracle upon miracle,” Scully said. “I don’t know in retrospect how I didn’t break down and begin to cry because Larry hit a home run. So, if you want to talk about the truth being stranger than fiction, that’s it — from the back row of the auditorium on the campus of Fordham University to a home run at Ebbets Field about eight years later. I’m describing the home run we thought was impossible. A one-in-a-trillion event.”

Post script: Miggins lived to be 98 years old when he died in December of 2023 in Houston. His story was captured here in 2021:

== July 4, 2024: Another Mark Langill moment: He is speaking to a group who attended a Fourth of July event at a middle school in Malaga Cove area of the Palos Verdes Peninsula, honored for his work as the team historian. Langill has this story about Scully to share:

“They always say be careful of meeting your heroes because you might be disappointed. … But when you finally meet Vin Scully, and you realize, oh my gosh, he is even greater than you even thought. All the preparation he would do (for a game) would be about that thick (holding his hand up to show at least three inches of material). You’d be in the booth and after the game you realized he didn’t use any of it! Maybe a little bit here and a little bit there. You realize that was his genius. It was a spice, and it wasn’t a crutch. He was prepared for everything, but then he would just let it play out. I asked him once: What is the secret to your success as far as your philosophy? You have a million people hanging on your every word. And he quotes Laurence Olivier, the actor. Most people don’t even know who Laurence Olivier is. He said: Have the humility to prepare, and the confidence to pull it off.

“Toward the end of his career, he would be perfectly dressed. In the press box, he would laugh and say: ‘These are my distractions.’ What he meant by that is, when you’d see him, you’d see the beautiful tie, the pocket kerchief with matching socks, elegantly pressed suit, and he said: ‘That way, you see someone who is well dressed and they forget the person they’re looking at is 86 years old’.”

== Aug. 3, 2022: George Vecsey had stopped writing his “Sports of the Times” column for New York Times in 2011, but the newspaper asked him to pen a piece on the passing of Scully from the perspective of his youth as a Brooklyn Dodgers fan.

“One consolation for the heartbroken Brooklyn fans left behind by the Dodgers was that Scully remained within earshot,” Vecsey wrote in his piece. “He called World Series games often enough that we could be reminded of what we had lost. Gil Hodges and Duke Snider came to the Mets as faded icons, but Scully would materialize on the air waves at the peak of his game.”

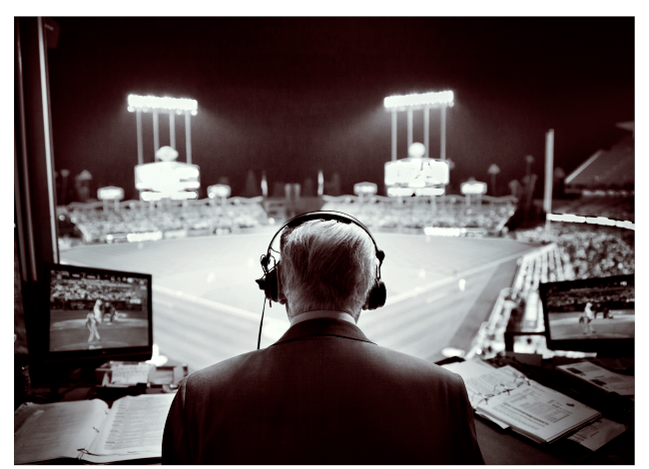

But weeks later, Vecsey followed up on his GeorgeVecsey.com website with more background on a story about a photographer who captured what he thought was one of the classiest photos of Scully doing his work in the broadcast booth, titled: “What Scully Saw; What the Photographer Saw.“

The piece started with Vecsey seeing his story the next morning when the New York Times arrived in his driveway:

“My column was accompanied by a lovely photo of Vin Scully, from behind, as he called a night game at Dodger Stadium. … The photo by Dominic DiSaia perfectly demonstrated the link between Scully and his fans since the Dodgers moved to LA in 1958. (I’ve gotten over it; oh, yes, I’ve gotten over it.)

“The photo in the glowing night demonstrated the link between a grand franchise and the mellow, knowing, professional voice of Vince Scully. The fans in Dodger Stadium are one thing, but the audience ‘out there’ is also tangible.

“We saw the stadium and sensed what was beyond, from the back of Scully’s fertile head.”

Vecsey learned that DiSaia was a freelance commercial sports photographer from Southern California. In 2013, he proposed a project for ESPN about a day in the life of Vin Scully, which allowed him to follow Scully around — but not at home, just at Dodger Stadium, and nothing during the game.

“He wasn’t too thrilled about it,” DiSaia told me over the phone, a note of admiration in his voice. “He was a very private man.”

DiSaia snapped away, and then he got lucky. One of the aides in the broadcasting booth area told him that the seventh-inning stretch was a bit longer than normal breaks, and he let DiSaia slip into the aisle behind the broadcasters.

DiSaia stood behind Scully and saw the big picture – the broadcaster and his audience, in the stadium and wherever that broadcast went. As the Dodgers began batting in the home half, DiSaia snapped away, and then slipped out into the corridor.

After the game, DiSaia caught up with Scully for the promised wrapup photo, in the parking lot – but Scully did not want a glimpse of his actual ride home. He had a driver, because by that time Scully was not driving at night.

So Scully went off into the night, and DiSaia polished his photo essay for ESPN.

DiSaia has the photo for sale at his website.

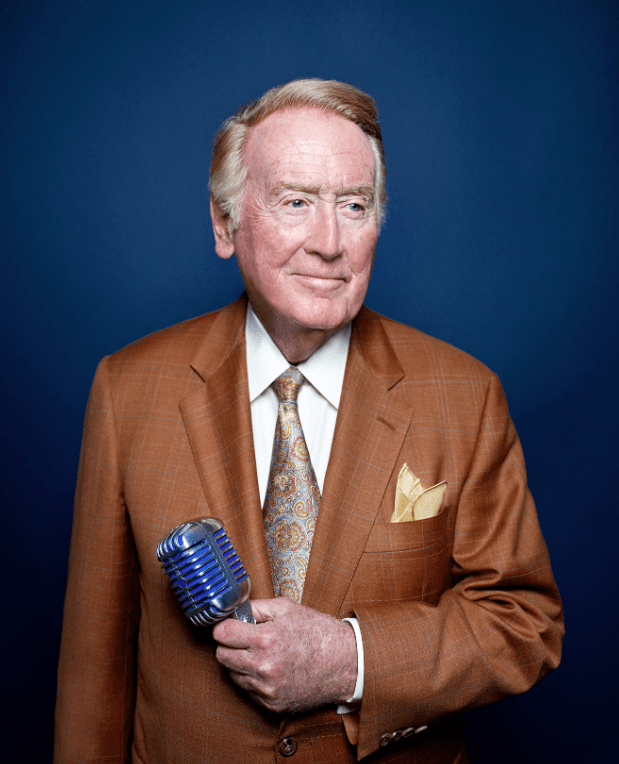

On DiSaia’s site is also this shot he took of Scully:

== Aug. 3, 2022: The Washington Post’s Jason Gay has a tribute that includes:

Let’s be honest: Any written appreciation of Vin Scully is going to be inadequate. You really need to hear him. Hear the sound, the enthusiasm, the melody that made Scully’s honey-covered voice the music of endless baseball summers. There was nothing like Vin Scully, and never will be again.

In person, Scully was as warm as you’d hoped he would be, impeccable in a blazer, his red hair trim and perfect. To be around Scully made a person sit a little straighter in the chair. He was the undisputed mayor of Chavez Ravine, who knew the name of the chef serving press box cupcakes, and nodded knowingly to Fernando Valenzuela, now a broadcaster himself, in the elevator.

Not long after our brief meeting, I got a phone call from an unknown number, and I let it slide over to voicemail. Shortly afterward, I listened to the message and it was Scully, just saying hello, checking in, in that unmistakable honey-covered melody that defined a sport for generations. It felt like a beautiful gift. As was the life of Vin Scully.

== Aug. 3, 2022: Joe Posnanski on his Substack platform included this in his tribute:

“We loved him most for being there, always, night game after night game, day game after day game, continuously finding a new story to coax a smile, a new description that caught us just a little bit by surprise, continuously finding the same level of delight he had been feeling for 70 years of calling baseball games … and other sports, too. … I told him then, as I had told him many times, about the goosebumps he had given me through the years. And I asked Vin one last time how he had done it, how for seven decades he had found the right words, how for seven decades in every situation imaginable he continuously found his exuberance and curiosity and sense of fun.

“ ‘Something does come up,’ he said of all those moments through all those years. ‘I really think God has had a hand in it. I really and truly do.’

“Rest in peace, Vin.”

Post script I:

In his 2023 book, “Why We Love Baseball: A History in 50 Moments,” Posnanski channels three specific calls that Scully made during his career that fit into the title’s theme: The 1965 Sandy Koufax perfect game, the 1988 Mets-Red Sox Game 6 finish and the 1988 World Series Game 1 Kirk Gibson home run.

Then, Posnanski saves his No. 1 essay on the call of Henry Aaron’s 715th home run on April 8, 1974, a game in which the Dodgers, and Scully, were an integral part of the event. Posnanski instead focuses on Milo Hamilton’s call – “There’s a new home run champion of all time, and it’s Henry Aaron.” – describing it this way: “Of all the wonderful broadcasting calls in baseball history I’ve always had a place in my heart for Milo Hamilton’s because – and I say this with all the love in my heart – it’s so uninspired. He obviously wanted to let the moment ring. He just blurted out words.”

And Scully basically recited a Gettysburg Address when he said:

“What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron.”

Post script II:

In the spring of 2024, Posnanski did a list of “The 50 most famous baseball folks of the last 50 years.” Forty seven of the 50 were players. One was manager Tommy Lasorda. One was Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. But the highest-ranked non-player: Vin Scully, at No. 33 on his list between Dwight Gooden and Mike Trout (and No. 23 on the list that readers filled out beforehand).

Posnanski wrote: “The voice of baseball for 67 seasons, he held the rare distinction of being as beloved nationally as he was in his Los Angeles hometown. He began broadcasting the Dodgers in Brooklyn in 1950 and retired in 2016, when he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Author of too many famous calls to count, although he preferred, in the most remarkable moments, to stay silent and let the crowd tell the story.”

== Nov. 1, 2024: After the Dodgers won the 2024 World Series, Ventura County Star columnist Woody Woodburn re-ran a piece he did from 2022, after Scully’s passing, that included:

Scully’s geniality in person was as authentic as it was on the airwaves.

“I enjoy people, so I don’t mind autograph requests at all,” he told me. “Why not sign? They’re paying me a compliment by asking.”

And what were some of the stranger “compliments”?

“I’ve signed a lot of baseballs, as you can imagine,” he shared. “But also golf balls and even a hockey puck, which is sort of strange. Paper napkins seem popular, even dirty napkins — I think it’s all they have on hand. I don’t expect them to keep it, but I sign anyway because hopefully they will keep the moment.”

How many magical moments did Vin — didn’t he make us all feel like we knew him on a first-name basis? — give us during his 67 years behind the Dodgers’ microphone? Count the stars in the sky and you might have the answer.

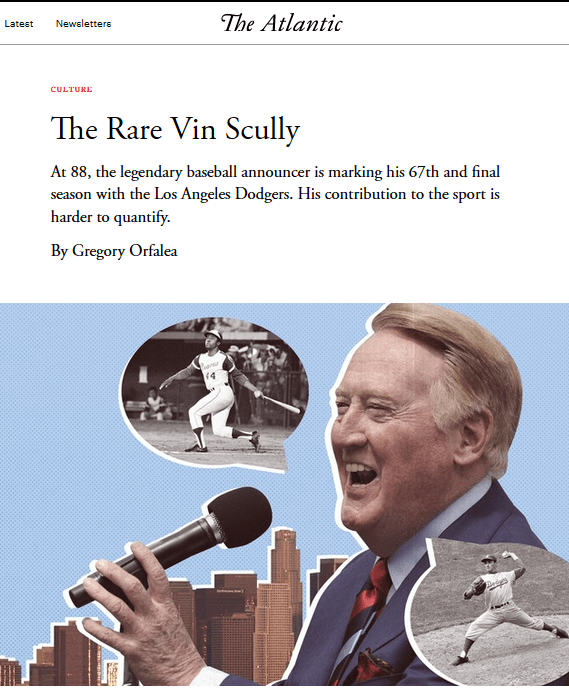

== April 24, 2016: An exquisite piece found in my favorite publication, The Atlantic, by Gregory Orfalea titled “The Rare Vin Scully.”

Ofralea starts by describing how he was a 12 year old selling frozen chocolate malts at the Los Angeles Coliseum in 100-degree heat August of 1961, frightened beyond his years in his first job, but somehow comforted by hearing Scully’s voice permeate through the stadium.

He writes:

“The voice seemed to come out of the earth. It was cooling in the heat, a sort of collective whisper that I felt was heard by my ears alone. It was Vin Scully. How could this be? Many a night, a sleepless asthmatic, I’d heard Vin’s voice through a transistor radio held to my ear in bed, with his lilting call of a Dodger home run—“Back goes Mays, a-Way Back, to the wall, SHE—IS—GAWN!” And I knew two things: a Dodger home run was a woman. And my lungs would unstick themselves at the roar of the crowd and Vin’s voice. I would awake the next day, the grill of the transistor imprinted on my cheek.”

He adds:

“Why is he so lionized? The answer, I think, partly lies in the nature of Los Angeles itself, spread across 502 square miles seeking a center, and its long-suffering life without baseball. … Angelenos latched onto him like a long lost cousin, a unifier the burgeoning town of suburbs desperately needed. New York had the Empire State building. Los Angeles had a voice. The voice.“

And this:

“Beauty comes from loss (and as Keats reminds us, there’s truth involved). You can’t earn it outright or even attract it. That clear, dulcet tenor, with its occasional tremor, was Scully’s gift from his red-haired, “excitable” Irish mother, as he described her. You couldn’t teach it, any more than you could teach Ruth and Aaron to hit baseballs far from home, to go home. (Baseball, after all, is about going home.) It was a born gift, yes, but the voice that raised L.A. was also loss-made.

“That blistering day in 1961 I also learned something about loss — it sold frozen malts. The Dodgers were shut out twice that day, 8-0 and 6-0, by the Cincinnati Redlegs (renamed during the ’50s’ Communist “Red Scare,” soon to return to just plain Reds). As the heat climbed and the people sweated, the malts practically flew out of my box. Save one. That one I savored alone, positioning myself right behind home plate, at the last out, and as his voice got fainter, I looked up behind me at the open booth above where the man with hair like a flame and the voice we all loved removed his headphones, took off his glasses, and went to the water cooler. I wished I’d kept one for him.”

And this gem:

“After my year-long attempt to secure an interview with him for this story failed, just after New Year’s I saw a message on my cell phone: Restricted. Listening, my ear widened: ‘Hi, this is Vin Scully trying to reach Or-FA-la. Mr. Or-FA-la, I’m sorry that it’s taken me so long to reply to your letter. Things are getting a little hectic this time of year for me and the family. But anyway, I just wanted to say hello and wish him well and acknowledge the fact that I certainly appreciate his lovely letter. Again, my regrets it took so long, but I send along my warmest wishes. Thank you’.”

== May 6, 2024: Jenny Cavnar, MLB’s first woman play-by-play broadcaster when she joined the Oakland Athletics’ TV team in 2024, explains the backstory of naming her son Vincent after Vin Scully, and the letter she received from him:

“I found out in 2017 I was pregnant, we found out we were having a baby boy and we were going back and forth on names. Really, the only name we could agree upon was Vincent, because I brought it because Vin Scully was because I’ll never forget that feeling or the emotion you feel in his presence. It’s the same when you get to know him in person. He just envelopes the idea of being a gentleman to me and if you could raise a boy to be that way in society, that’d be so cool. I brough it up to my husband (Steve Spurgeon, who played in the White Sox organization), who grew up a Dodger fan, listened to Vin Scully, and we agreed upon a name and I was able to let Vin Scully know in a Christmas letter.”

== June 11, 2014: Honestly, how much more presidential could Vin Scully look than when he did an hour-long presentation at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum in Simi Valley three years before his retirement?

Even the Reagan Library archives has filed away a clip of the time the 40th U.S. president joined his former Pacific Palisades neighbor, Scully, to call the first inning of the 1989 MLB All Star Game in Anaheim, which included Bo Jackson’s lead-off home run.

== March 8, 1997: Kevin McKenna of the New York Times did a piece about the Dodgers’ 50th season in Vero Beach, Fla., as their spring training home. Vin Scully had been there for almost all of them and explained:

”I don’t believe Vero Beach would be known anywhere outside of Vero Beach except for the presence of the Dodgers, ‘When I first arrived (in 1950), we stepped off the train and, my gosh, it was a tiny, tiny, somewhat dusty little Southern town. But as the Dodgers settled in, as the word went out, the Dodgers truly put Vero Beach on the map.”

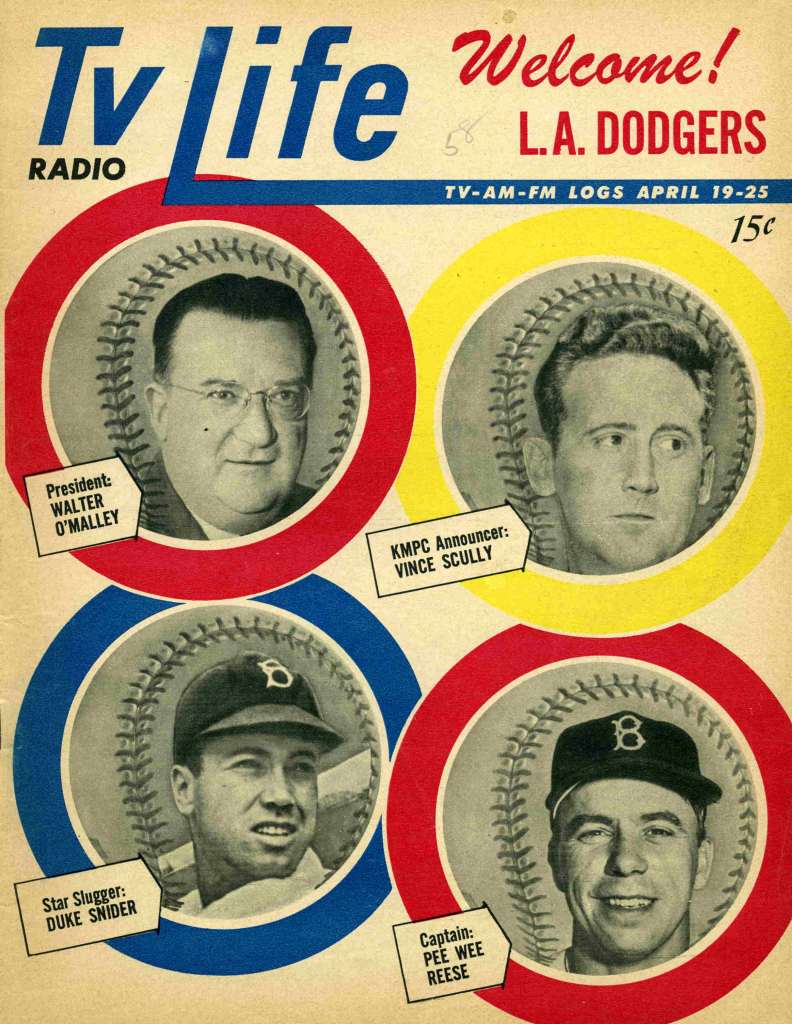

== April, 1958: The cover of TV Radio Life magazine welcomes the new Major League Baseball team in town:

== Aug. 3, 2022: James T. Keane of America Magazine: The Jesuit Review wrote at the time of Scully’s passing:

Scully … had a breadth of religious and cultural knowledge that spanned far beyond the limited range of your usual play-by-play man. To be fair, it spanned far beyond that of most priests, politicians and professors.

When he wasn’t on the air, Scully sometimes revealed the worldview behind the public persona. “Being Irish, being Catholic, from the first day I can remember, I was told about death,” Scully told columnist Bob Verdi in 1986. “Death is a constant companion in our religion. You live with it easily; it is not a morbid thought. That has given me the perspective that whatever I have can disappear in 30 seconds. And being out on the road as much as I am, I realize I am killing the most precious thing I have—time. You never know how much of it you have left.”

Over the decades, it wasn’t just Vin Scully’s quick wit, easy erudition and pleasant demeanor that made him a legend: It was the voice itself. When I was in college, I got to meet him once at a benefit dinner where I was working as a waiter. I snuck up to his table and introduced myself (he was charming), and suddenly there it was: The Voice.

== A YouTube clip: Vin Scully reads a grocery list, done in 1982 when asked by San Diego Padres’ team official Andy Strasberg:

== A YouTube clip: From a Dodgers game in 1986, where Scully can’t believe the team’s inability to play — and watch how Greg Brock allows him to express himself between two swings and misses before reinforcing the theory:

== July 29, 1969: Among the various games one can find on YouTube’s “Classic Baseball on the Radio” subscription, this one makes the cut from Wrigley Field. It’s Vin Scully and Jerry Doggett calling a game where the Cubs’ Ferguson Jenkins goes up again the Dodgers’ Don Drysdale.

At the 21-minute mark, right after Jenkins issues a walk to the Dodgers’ Bill Sudakis, Scully says this as a way to mark the broadcast and allow 10 seconds for station identification.

“Well this Dodgers-Cubs broadcast is coming from Chicago.

“You know, when your telephone rings, it’s a good idea to try to answer it as promptly as possible. It’s thoughtful and courteous and it’s a good way to make sure your caller doesn’t hang up.”

Now, back to the game …

== March 29, 1991: A Los Angeles Times story revisited the 10th anniversary of “Fernandomania.” So, where did that phrase even come from?

No one remembers who coined the word ‘Fernandomania,’ but the odds are that it was Vin Scully. There was a mystique about this pudgy kid from Echohuaquila, a small village in the state of Sonora, Mexico.

“He had long hair, he looked old, he did everything right–it all added to the mystery,” Scully said. …

“I’ve said this before, and I say it in measured tones, but the 1981 season and Fernandomania bordered on a religious experience. Fernando being Mexican, coming from nowhere, it was as though Mexicans grabbed onto him with both hands to ride to the moon.

“I would see parents who would bring their children to the ballpark, not only to show them how good Fernando was, but as if to say, ‘See, if you work hard, even if you are poor, you can succeed.’ There was a fervor about his being and the reaction of the crowd was like nothing I have ever seen before. I’ve seen great pitchers and cities who love players. But I have never seen anything like this, and I don’t think I will ever see it again.“

== Aug. 5, 2022: PBS SoCal once aired a documentary “Dodgers Stories: 6 Decades In L.A.“ and included a segment on Vin Scully. Victoria Bernal posted “13 Vin Scully Highlights Captured in Southern California Archives.”

It included a link to a transcript from what some fans had to say about Scully. Bernal’s piece also included:

= In 2017, the Library of Congress posted an interview as well as added a Scully recording from 1957 to its prestigious National Recording Registry “as an aural treasure worthy of preservation.” The recording features Vin Scully calling the last game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants at the Polo Grounds on September 8, 1957 before moving to California. Scully says:

“I don’t know how you feel about it at the other end of these microphones, whether you are sitting at home, or driving a car, on the beach or anywhere, but I know sitting here watching the Giants and Dodgers apparently playing for the last time at the Polo Grounds, you want them to take their time.”

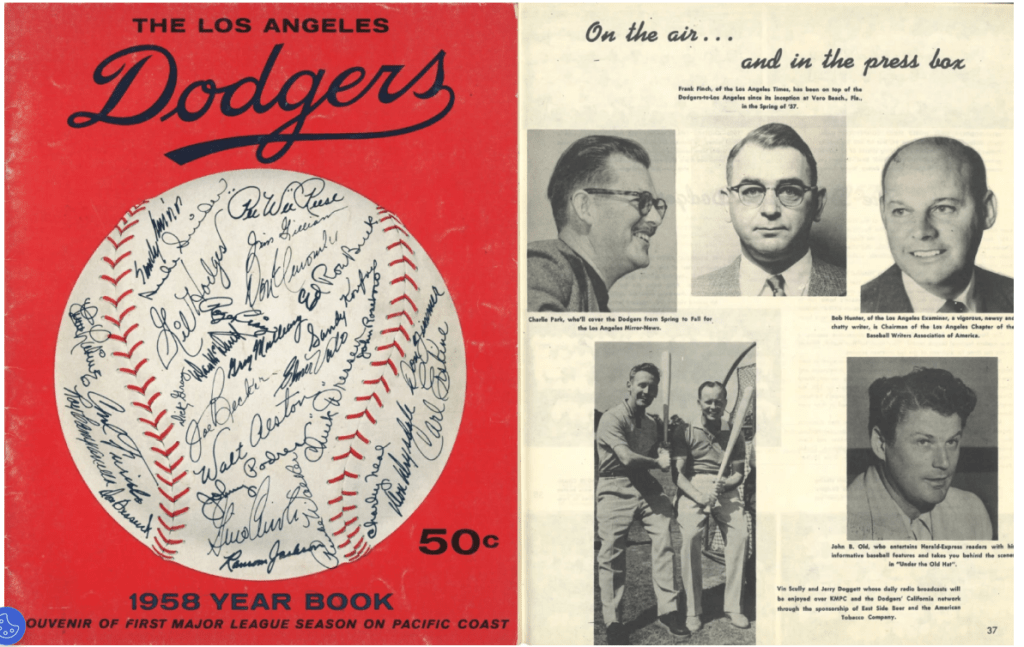

= From the LA84 Foundation came a copy of the first L.A.-based 1958 team yearbook, which included Scully and Jerry Doggett on page 37 almost as an afterthought of the media who would be covering the team from the L.A. Times, L.A. Mirror-News, L.A. Examiner and Herald-Express. It captions the two new voices as: “Vin Scully and Jerry Doggett, whose daily radio broadcasts will be enjoyed over KMPC and the Dodgers’ California network trough the sponsorship of East Side Beer and the American Tobacco Company.”

== During the 2020 shutdown because of the COVID pandemic, Twitter posts @TheVinScully helped many of us just get through the isolation. It likely helped him as well.

This is one of our favorite posts:

That high school photo of Vin reminded us of another photo we came across, from June of 2009, from SonsOfSteveGarvey.com fan site.

Chad Scully, the then-15-year-old son of Vin’s oldest son, Michael, is shown as a Dodgers’ ballboy sitting on the bench next to Dodgers manager Joe Torre.

The resemblance is fascinating.

Michael Scully was killed in a helicopter crash at age 33 in January of 1994. He was an civil engineer inspecting a crude-oil pipeline that runs from the San Joaquin Valley to Southern California, looking for earthquake damage after the massive 6.6-magnitute Northridge Earthquake.

That afternoon of the crash, Vin and his wife, Sandy, left Burbank Airport flew to Bakersfield to be with Michael’s wife, Kathy and their 3-year-old son, Matthew Vincent Scully, 3. The jet brought them all back to Southern California the next day. While in the air, Kathy, who was pregnant, went into labor. After the plane arrived in Burbank, she was taken to St. Vincent Hospital, with Vin and Sandy Scully accompanying her.

Soon, Chad Michael Scully was born, a bit premature. Three days after the birth, Kathy Scully attended her husband’s funeral services in Brentwood.

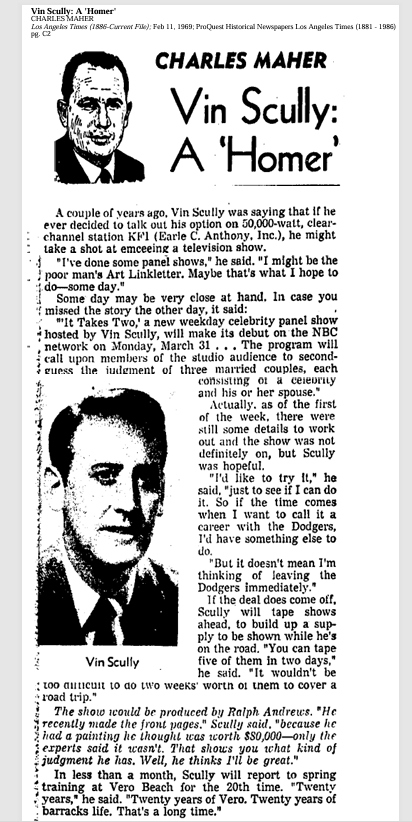

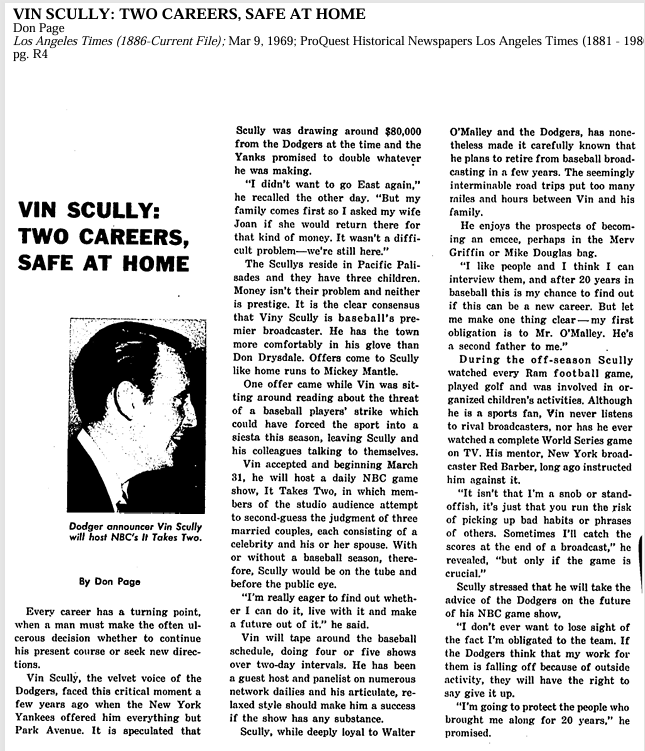

== 1969: In February and March of that year, the Los Angeles Times ran columns about Scully’s new attempt at hosting a TV show.

“I might be the poor man’s Art Linkletter,” Scully told the Times’ Charles Maher. “Maybe that’s what I hope to do — some day … I’d just like to try it, just to see if I can do it. So if the time comes when I want to call it a career with the Dodgersrs, I’ll have something else to do. But it doesn’t mean I’m thinking of leaving the Dodgers immediately.”

Not for another 47 years at least.

Scully told the Times’ Don Page that a threat of a baseball strike got him to thinking about other gigs, leading to hosting NBC’s game show “It Takes Two.”

“But let me make one thing clear — my first obligation is to Mr. O’Malley. He’s a second father to me,” said Scully about his Dodgers priorities … I’m going to protect the people who brought me along for 20 years.”

== Aug. 11, 2024: An essay in the New York Times magazine by Gregory Barber titled “How to Fall in Love With Baseball: Radio play-by-play taught me about the game’s stark beauty — and who my grandmother was” included this:

The hallmark of a great baseball radio announcer is knowing when to remain silent. That way, the game speaks for itself. …

When you listen to baseball on the radio, you learn that there can be beauty in redaction, in going by only what you’re given. The late, legendary Vin Scully, who called games for the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles on both radio and television, renders the final inning of Sandy Koufax’s 1965 perfect game immortal via restraint. He describes Koufax taking the mound — “the loneliest place in the world” — with “29,000 people in the ballpark and a million butterflies” surrounding him.

Scully has you observe closely, at first — Koufax wiping a finger on his pants, tousling his hair, fussing with a cap. Then he goes wide, sending you into the crowd. After calling the last strike, he’s silent for 39 seconds.

Not every game is a perfect one, and dead air is usually dangerous. The listener needs to know what’s going on. … The game comes in and out of focus, just as it would if you could be in the stadium yourself. Certain moments nail your gaze to the field; others provide the opportunity to wander off in search of a kielbasa. Greats like Scully knew this.

My grandmother listened to Scully call the Brooklyn Dodgers before they broke her heart and moved West in 1958. She was an Irish Catholic who professed to see spirits living inside you and whose leftist politics were forged in a household that sent envelopes of cash to the I.R.A. As a young woman in Albany, she approached baseball fandom as she approached everything else: with fervent devotion. It was not in her being to root for the Yankees. ….

After college, I followed her childhood team out West. A decade passed, and her generation disappeared. The minds and bodies of the next generation began fraying, too — and for those left, so did the last chances to connect ideas about ourselves to stories of people who actually existed. So I find myself doing what she did, hunting for the broadcast, a stage shared by generations, listening for what made her, and therefore me, a fan.

== Sept. 23, 2016: Prior to the Dodgers’ 5-2 win over the Colorado Rockies at Dodger Stadium before some 52,320, with the sounds of “Field of Dreams” playing in the background, Kevin Costner delivered a nearly 10-minute speech. I considered transcribing it for the book, but wanted to pursue an original essay instead. The speech remains available to watch again. The comments include:

You were better than a golden ticket. You invited us all to pull up a chair, spend the afternoon, and then proceeded to walk us into the next century. You did it in a style so friendly and unique, so effortless that years from now we will not be able to explain it to those that never heard it for themselves.

The game will not lose its way. But it loses a perspective, a singular voice that managed to capture a boy’s game played by men at the highest level. You grounded it in a way no one else ever has, trusting that you never had to make more of any one moment than it really was.

For 67 years you managed to fool us into believing you were just a sports announcer when fact you were really a poet. A wordsmith. It was a nice trick. And after almost seven decades, you might have thought we would have caught on. But now the masquerade is over. The jig is up.

And if anyone ever wondered what it might feel like to have Vin Scully call your name, I can tell you for sure that it must be something close to heaven. I wasn’t a player but in ‘For Love of the Game’ I had that moment. You called my imaginary name and my imaginary perfect game and no one can ever take that away.

You’re our George Bailey. And it has been a wonderful life. (Cheers).

So don’t blame us, don’t blame us for wanting to push the sun back up into the sky one more time. For asking God to give us extra innings in a Dodger win. You can’t blame us for trying to hold onto you as long as we can. And you can’t stop us from saying that we love you.

So live your life, Vin. Live your life and see the world with your sweetheart and shame on us if you ever have to pay for another meal in public.

My editor’s note: On the Saturday afternoon after the ceremony, Scully chatted with reporters in the press box about the previous night. I mentioned to him that he really looked moved by what Costner was saying.

Scully admitted: “Honestly, I couldn’t hear him very well. The feedback from the speakers were delaying the words and I was right next to him so I could hear him say something then it would reverberate … I think what you saw was probably a look of confusion on my face as I was trying to figure it out.”

In June of 2018, Costner appeared on the Rich Eisen Show and said this abut the brilliance of Scully when it came to doing dialogue for the movie “For Love Of The Game”:

“He came into the studio and the director says, ‘This is Vin Scully, hello and this is the movie and here is some lines.’ (Vin) says: ‘Could you just show me the film?’ They played six minutes. He said: ‘Why not just let me take a shot at this?’

“He starts saying the stuff that’s in the movie. It’s like a songbird. He got through it and I looked it at it — and the hair on my arm is standing up. The director says: ‘Do you want to run it again?’ And Vin says: ‘Do we need to?’ ‘Well, maybe something more will come.’ ‘All right.’ He looks at me. I shrug. It was his prerogative. But Vin did something to it again and the director was right. And I have it forever, right?

“I got a chance to do a speech for at his farewell at Dodger Stadium. It was a big moment. I got the word from him: I’d like to have Sandy (Koufax), Kirk (Gibson) and Kevin. There’s got to be 100 people who need to be on this field. He called me ‘Kevie.’ It was just us three. Kirk couldn’t be there. But when I got up, I found what I wanted to say about him. I was thinking about everyone who felt something about him and I felt I was talking for them.”

In August of 2022 after Scully’s passing, Costner told a similiar version of the story for a LiveTalksLA presentation when moderator Ron Rapoport was joined by Costner and Ron Shelton:

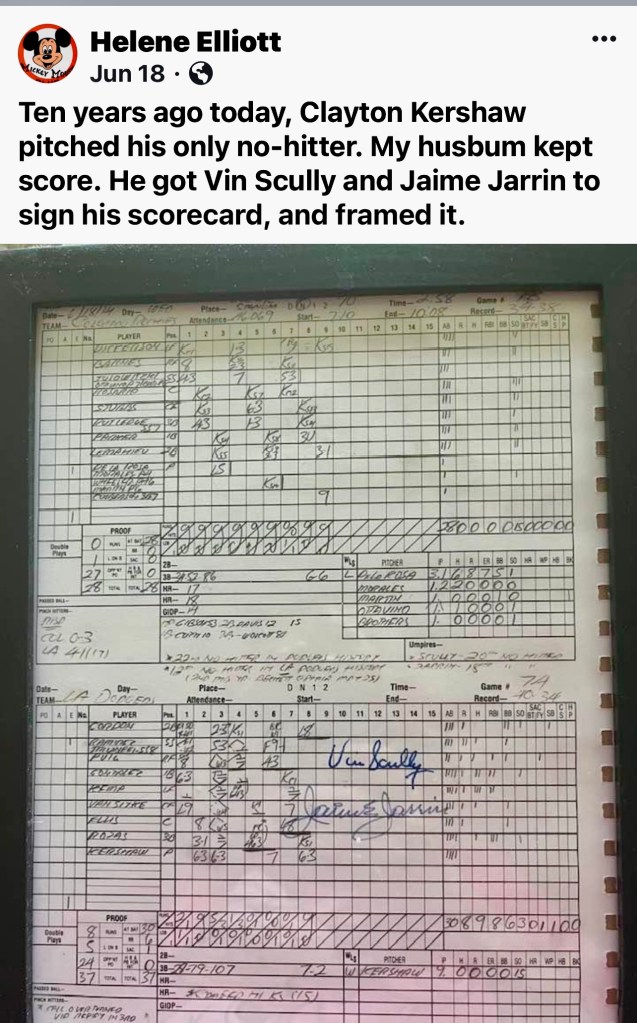

== Social media posts like these are always pretty darn cool, from June 18, 2024. Helene’s husband, Dennis D’Agustino, was one of the team’s official scorers, so it’s even more cool.

Dennis was responsible for a couple of Dodgers-related books, such as “Through a Blue Lens: The Brooklyn Dodger Photographs of Barney Stein 1937-1957,” which we reviewed when it came out in 2007, noting in particular a certain Scully photo of him in the dugout, holding a cigarette, talking to Gil Hodges … and we later embraced his book called “Keepers of the Game” he wrote in 2013 with this review):

== A Sept. 2, 2016 essay by George Will for The Washington Post titled “Baseball’s storyteller, our friend.” The highlights:

“Although he uses language fluently and precisely, he is not a poet. He is something equally dignified and exemplary but less celebrated: He is a craftsman. Scully, the most famous and beloved person in Southern California, is not a movie star but has the at-ease, old-shoe persona of Jimmy Stewart. With his shock of red hair and maple syrup voice, Scully seems half his 88 years. … In this era of fungible and forgettable celebrities, he is a rarity: For millions of friends he never met, his very absence will be a mellow presence.”

== A Sept. 22, 2016 essay by Keith Olbermann for GQ magazine titled “Vin Scully Is A Legend, But He’s Not A Saint.” The highlights:

“As the years have piled up he has gone from being Brooklyn Boy Wonder Announcer to Inventor of Los Angeles Baseball to The Game’s Greatest to Icon to Saint Sportscaster to, this year, something approaching Living Deity.

“This is not to say Vin Scully is not a terrific and endlessly patient human being, nor that anyone who has treated him with reverence, nor that the succession of ballplayers and managers who have bestowed the ultimate role-reversal praise by making the pilgrimage in full uniform to him in the press box are being insincere or overdoing it. It’s just that the real Scully … is far more human and far more capable of the unexpected. And thus far more praiseworthy. He’s not as good as everybody’s making him out to be — he’s better.”

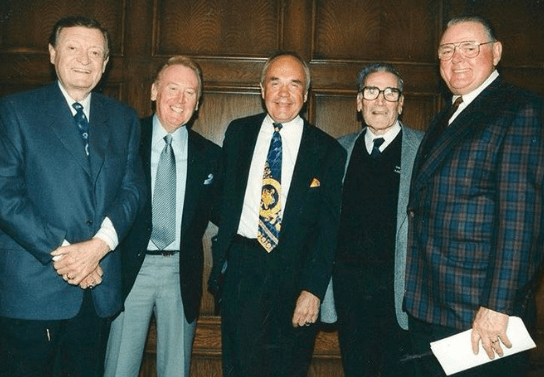

== On Aug. 3, 2022, New York Yankees broadcaster Michael Kay (pictured above with Scully and Olbermann) wrote this for the New York Post:

I had the opportunity to meet him on April 4, 1999, when the Yankees were in Los Angeles to play the Dodgers in an exhibition before the start of the season.

As I debated how I would approach Vin, I saw Scully’s longtime friend, Keith Olbermann, and he graciously said, “I’ll introduce you.” And immediately, Scully made me feel as if he had known me for years. He immediately disarmed me with stories and spoke about our connection, having both gone to Fordham. In a moment, he was a friend, and his demeanor told you that he was happy to meet you and actually was delighted to spend time talking.

The piece concluded:

The broadcasting business is full of some of the biggest egos that you can ever imagine, yet there is no one with the hubris to even think he or she is as good as Vin Scully. No one.

And in a business with its share of vipers, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone that has a negative thing to say about this man.

He was that special.

Personally, I am honored to have used the same studios at Fordham’s WFUV as Scully used in the late 1940s. A generation of Fordham broadcasters view Scully as the patron saint. He is ours. And when we have playful debates with our Syracuse friends about each school’s assembly line of broadcasters, all of us simply say, “Vin Scully went to Fordham” and we dramatically drop the mic. No one tops Scully. Game over.

== A 2018 book titled “LA Sports: Play, Games and Community in the City of Angels,” edited by Wayne Wilson and David K. Wiggins (University of Arkansas Press, 362 pages) ends with chapter 15 by Elliott J. Gorn and Allison Lauterbach Dale called “Vin Scully: The Voice of Los Angeles.” It was originally published in “Rooting For the Home Team: Sport, Community and Identity” in 2013 (University of Illinois Press) and edited for this anthology.

It includes:

“Maybe most striking, in a city that routinely destroys all sense of tradition and history, that embraces each postmodern moment as distinct from the last, Scully is all about continuity. … We mark time and the big moments by memories of his broadcasts. Fifty years isn’t a long time in the course of human history, but for a town like Los Angeles, it represents a deep past. Not just longevity, but Scully’s devotion to baseball , made manifest in his formidable knowledge of the game, matters here, too … The children of immigrants from eastern cities, of dust bowl refugees in the 1930s, and of midwesterners whose opportunities on the land closed down as farms consolidated, must have heard him as a voice from home. But others too — African Americans who came from the South in search of equality, jobs and schools for their children in the 1940s and 1950s; Asian immigrants and their descendants for whom midcentury California began to fulfill earlier promises; Mexican American kids whose parents sought fresh opportunities for their families — all had some familiarity with baseball but came to think of it as quintessentially American. Scully’s easy presentation of the game was tied up with the promise of California life. … I often go back to L.A. because my daughter lives there. There is nothing like hearing Vinny still calling games. I’m not a big fan of Southern California, but his voice somehow captures what is best about the place, the ease and flow of outdoor living, the beauty of mountains and desert and ocean. There is grace in Scully’s cadence, just as there is grace in that mellow landscape in the twilight glow.”

And that is how the book ends.

== A 1956 book titled “Famous American Athletes of Today: Fourteenth Series,” by F.E. Whitmarsh (L.C. Page & Company; 308 pages) contains a chapter “TV and Radio in Sports.” It has this on pages 242-243:

“Best known of the modern baseball broadcasters is probably the old Redhead, Red Barber, who broadcasts games of baseball’s daffiest team, the Brooklyn Dodgers. Red Barber started to broadcast the Dodgers games in 1939 and is still at it — the longest broadcasting association in the baseball field. He has followed and faithfully portrayed the Dodgers under the general managerships of Larry MacPhail, Branch Rickey and Walter O’Malley … The Redhead has seen his beloved Dodgers advance from being the doormat of the National League to its champion. He has become such a distinct part of the Brooklyn scene that few fans remember he came East from Cincinnati to take over the Brooklyn Dodger job. … Hes still universally associated with the Dodgers and few Dodger fans can conceive of any other broadcaster doing that job. However, the old Redhead, like all of us, is growing a little older all the time and he’s gradually breaking in Vin Scully as a replacement.”

== In April, 2025, the Urban Dictionary included its first reference to the phrase “Don’t Scully me.” The website defined it as a reference to Dana Scully in the TV show “The X Files.”

“It’s when someone tries to use every excuse before the truth, to get out of something, or stick up for somebody or something. If you get caught cheating on your bf/gf and you try to make up every possible excuse you can think of, your bf/gf might reply: “Don’t Scully me.”

The truth is out there: Show creator Chris Carter told CNN in 1998 he created the red-headed character’s name in honor of Vin Scully:

“You know, Vin Scully was always the voice of God. When I was growing up my mom would fall asleep with Vin Scully in her ear on the pillow. I named (Gillian Anderson’s character) Scully after him. I’ve never been able to tell him that. I’m sure he knows now.”

And one of the responses from that tweet came from Scully’s daughter-in-law:

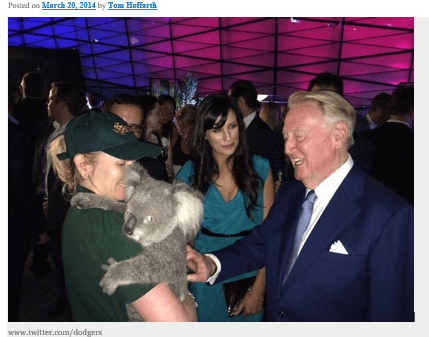

== March, 2014: I found a piece I did on Scully during the Dodgers’ trip to Australia titled “Pair up Vin Scully with a koala and how do you lose? Dodgers Hall of Fame broadcaster reports no fresh-water croc sightings this time.” After I tracked him down on the phone the day before the Dodgers and Arizona Diamondbacks were to start the season with a two-game series at the famed Sydney Cricket Ground, our conversation included:

“They’re really done a remarkable job with the park. You’d swear they’d been playing baseball there for a very long time. It looks very much like a major-league park, a double-deck stadium with the exception of an area down the first-base line that looks like something out of Churchill Downs during the Kentucky Derby. It’s a beautiful park to be in and it should be fun. And the people we’ve met so far have been very charming. They couldn’t be nicer.”

“The papers are bursting with news about cricket and rugby and football — whatever they call it here — and the coverage of baseball is not extensive at all … One of the papers here — one of those headline-seeking papers — had some sarcastic reference to the Dodgers’ salaries compared to the money paid to cricket players, naturally way out of whack. Another line from the story was about how the players had ‘strode through the airport with designer suits and sunglasses firmly on,’ which was nothing further from the truth, but they were trying to make a point.”

There was also the fact that the Dodgers’ new SportsNet L.A. cable channel was having trouble getting distribution. It was the only source for the Dodgers’ first two games of the season in Australia.

“I guess it will feel strange to know we’re not going to be seen by the big audience we always have,” he said. “But the first game will be at 1 in the morning in Los Angeles.”

== A 1964 piece by Robert Creamer for Sports Illustrated titled “The Transistor Kid” tried to explain Scully’s presence in Los Angeles some six years after leaving New York — and now actually being courted to move back to join the Yankees after the 1963 World Series where the country got to hear Scully and Mel Allen call a Yankees-Dodgers championship (the Dodgers swept in four games, and Allen was done as a broadcaster).

It included:

“This year, at 36, he is in his 15th season of broadcasting major league games, a statistic that is bound to startle anyone who ever heard Red Barber turn the mike over to Scully in the old Ebbets Field days with a cheery, “O.K., young fella. It’s all yours.” In the six years that he has been in California, Scully has become as much a part of the Los Angeles scene as the freeways and the smog. … Vin Scully’s voice is better known to most Los Angelenos than their next-door neighbor’s is. He has become a celebrity. He is stared at in the street. Kids hound him for autographs. Out-of-town visitors at ball games in Dodger Stadium have Scully pointed out to them—as though he were the Empire State Building—as he sits in his broadcasting booth describing a game, his left hand lightly touching his temple in a characteristic pose that his followers dote on and which, for them, has come to be his trademark. … When the Dodgers are playing at home and Dodger Stadium is packed to the top row of the fifth tier with spectators, it seems sometimes as though every member of the crowd is carrying a transistor radio and is listening to Scully tell him about the game he is watching. … Scully lives in a house that is a strikingly successful blend of eastern clapboard and California glass, on the side of a hill on a dead-end street (“In Los Angeles we say cul-de-sac,” Scully tells his New York friends) in the Brentwood hills. … People from New York ask me if I miss the East. I really don’t. I like Los Angeles. When I was in my 20s we moved from Manhattan out to a town in New Jersey, a very pretty town. But the people there sort of resented all the New Yorkers moving out and cluttering up their nice roomy suburb, and I couldn’t blame them. Well, that’s the way I feel about Los Angeles now. When my New York friends say, ‘I don’t see how you can live out there,’ I nod my head and say, ‘You’re right, it’s terrible, don’t move out.’ I don’t want things to change.”

== A 5,400-word piece for the Society of American Baseball Researchers is posted on the group’s website, written by Greg King.

It is a modified piece of what King wrote for the SABR Journal called “Vin Scully: Greatest Southpaw in Dodgers History” for the 2011 Baseball in Southern California Issue. The story references various Los Angeles Times stories, pieces from The Sporting News, Christian Science Monitor, and an interview with Scully from 1991.

It includes this quip from a Scully broadcast in 2010:

Despite his rise to prominence, having received virtually every national sports broadcasting award possible, including having the press box at Dodger Stadium named in his honor, Scully remarked many times that he was not special. He never took himself too seriously, perhaps illustrated in the following short recollection he told over the air.

“Wilver Stargell hit the first ball out of Dodger Stadium in 1969 off Alan Foster,” Scully recalled before asking his audience, “Who called it?” Scully then answered his own question with the confession, “Jerry Doggett — bless his heart. I was in the restroom.”

== From a March 1, 2023 story in Film Maker Magazine titled “We Aren’t Simply Trying to Appeal to Nostalgia”, where Jon Bois talks about the art of sports documentaries. Bois, the creative director for Secret Base, a YouTube Channel (with 1.3 million subscribers) that is part of SBNation.com, saidScully was the “hero and inspiration” for his work with co-writer Alex Rubenstein. He continued:

“When the action died down, as often happens in baseball, he would take the chance to tell a fun story from a month ago or from 40 years ago. Sometimes he would build these riffs that almost resembled short one-man plays. When he did these things, he was telling you that he wasn’t here simply to broadcast, he was here to talk to you. He wanted you to have fun.

“We’re not Vin Scully and we never will be, but in terms of the ability to speak to the person on the other end, he’s a North Star for us.”

== From a July 8, 1983 column the Los Angeles Times’ Jim Murray did on Scully. It includes:

“It took baseball in its wisdom 10 years to turn Babe Ruth, the most perfect hitting machine of all time, from a pitcher into a slugger. It took football seasons to figure out Marcus Allen wasn’t a blocking back and to hand him the football. And it took network television forever to get the message that Vin Scully should do major league baseball and stop fooling around.

“It wasn’t that Scully was inept at other sports. It was just that he was miscast. It was like Errol Flynn playing a faithful sidekick. Scully could do golf and do it well. Rembrandt could probably paint soup cans or barn doors, if it came to that. Hemingway could probably write the weather. Horowitz could probably play the ocarina. But what a waste! Nobody understands baseball the way Vin Scully does. He knows it for the laid-back, relatively relaxed sport it is. Scully is the world’s best at filling the dull times by spinning anecdotes of the 100-year lore of the game. He can make you forget you’re watching a 13-3 game, as we were Wednesday night at Chicago, and take you with him to a time and place where you are suddenly watching Babe Ruth steal home. He is like a marvelous raconteur who can make you forget you’re in a dungeon. He can make baseball seem like Camelot and not Jersey City.”

And then there’s an August 1990 piece Murray wrote called “The Greatest Dodger of Them All Never Wore a Uniform.”

It includes:

“Vincent Edward Scully meant as much or more to the Dodgers than any .300 hitter they ever signed, any 20-game winner they ever fielded. True, he didn’t limp to home plate and hit the home run that turned a season into a miracle — but he knew what to do with it so it would echo through the ages.

“Scully made an art out of baseball broadcasting. He also made journalism out of it. In a profession so full of “homers” — not the four-base kind, the kind where the guy in the booth root-root-roots for the home team — Scully distanced himself from partisanship.

“(In 1958), Scully sold Los Angeles on the Dodgers — with a team that finished next to last. Scully was the master at distracting attention from the inept, the boring. He didn’t broadcast a game, he narrated it. … Scully without the Dodgers was Caruso without an opera, any troubadour without a song. … The Dodgers are 100 years old. Scully has been with them almost 40. In that time, attendances of 2 million — thought impossible for a baseball franchise — became commonplace in Los Angeles. Then, 3-million attendances were achieved six times. Scully was there for all of them. It may have been a coincidence, but I think not. Scully will never be MVP — most valuable player. But he has to be MVD — most valuable Dodger.”

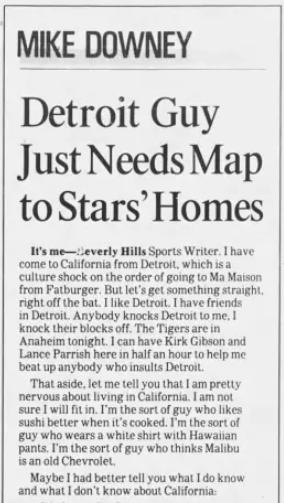

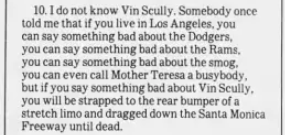

== The June 14, 2024 obituary for former Los Angeles Times sports columnist Mike Downey included a newspaper clip of the first column he wrote for the paper, coming from Detroit via Chicago, in 1984. He was explaining what he knew and didn’t know about this new place he would work for in L.A. and it included this:

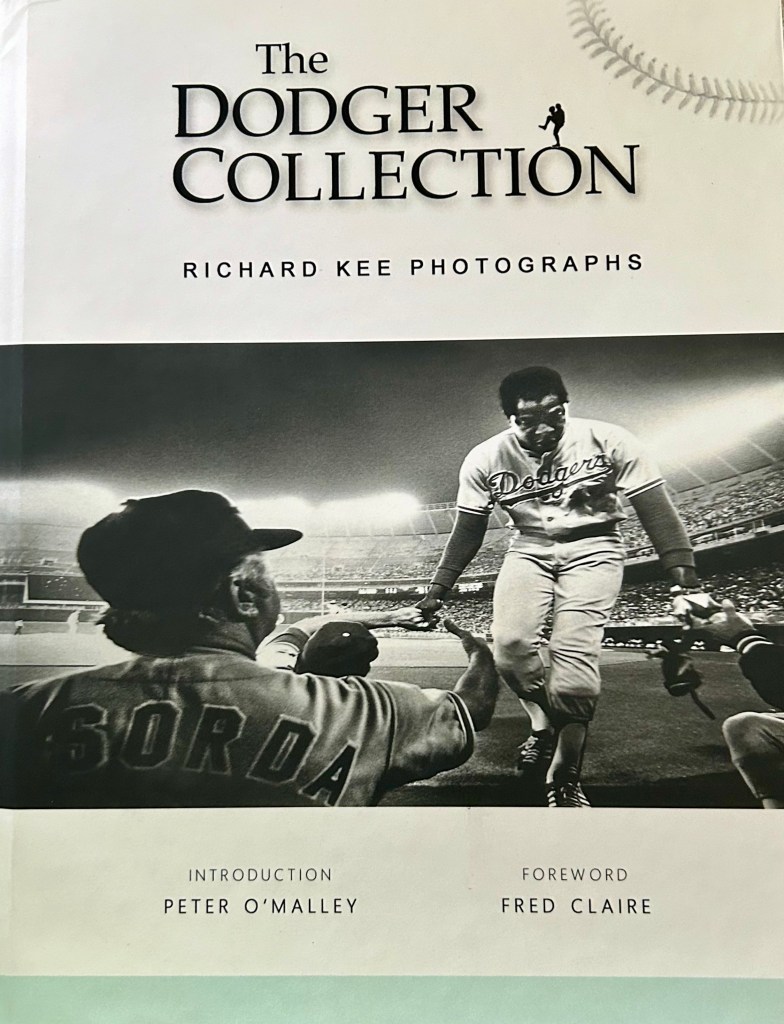

== In September of 2023, former Dodgers team photographer Rich Kee came out with a collection of his best work, called “The Dodger Collection” (Taylor Publishing; 188 pages; $39).

Here is a link to the book’s official website. Here is a link to a review we did on the book. Included is a shot Rich captured of Tommy Lasorda and Vin Scully having a laugh at the batting cage that says so much. Such a joyful moment.

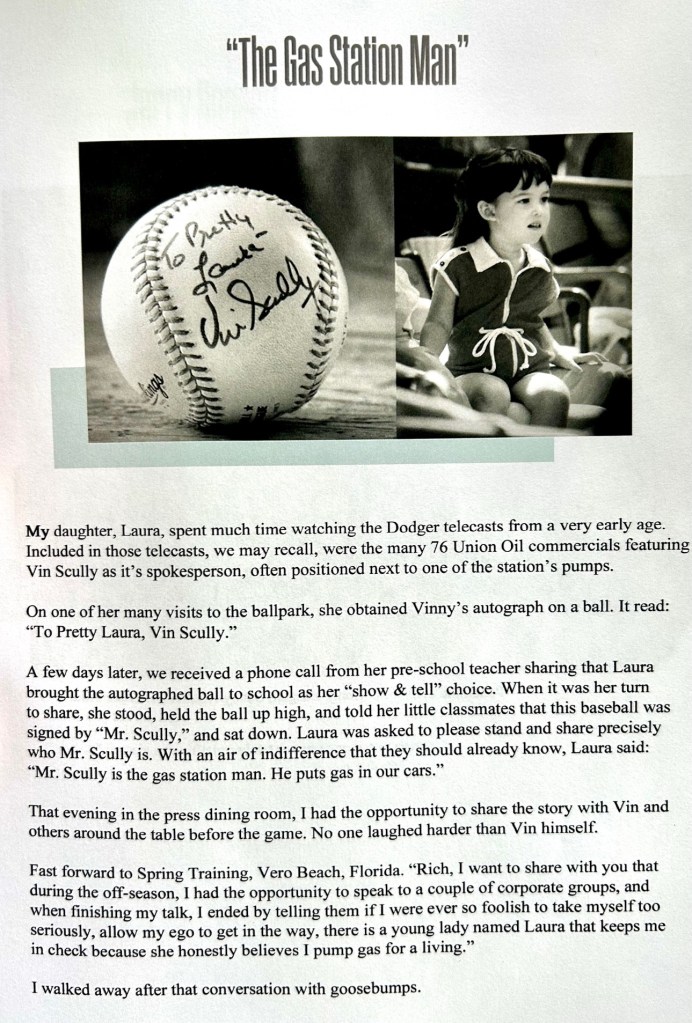

But make note of a story included about how Scully once signed a baseball for Rich’s daughter. She took it to preschool for show and tell.

It was also a lesson for Scully about how to stay humble, he later said when he heard Rich tell him about what happened.

The story went this way:

== June 19, 2024: A day after the death of New York and San Francisco Giants great Willie Mays at age 93, we were reminded that not only was it a treat for Vin Scully to meet up with Mays in the AT&T Park broadcast booth during the last two broadcasts ending his career in 2016, but the reason that happened was because Scully had often said Mays was his favorite player to watch.

According to baseball lore, Mays’ greatest catch came in the 1954 World Series at the Polo Grounds against Cleveland’s Vic Wertz, robbing him of extra bases, then whirling and throwing the ball back to the infield.

According to this account, Scully offered that there another great catch on opening day 1952: The Giants held a 7-6 lead against the Dodgers in the bottom of the ninth at Ebbets Field, two outs and the bases loaded. Brooklyn’s Bobby Morgan drove a line drive to center field. A hit would have won the game for the Dodgers.

“You hit the warning track, you hit your head on the concrete wall, you rolled over on your back holding the ball in your glove on your chest,” Scully recalled to Mays. “Henry Thompson came over, reached in, took the ball out of your glove, held it in the air and they called Bobby out. That was the end of the game. That’s the greatest catch, the greatest catch I’ve ever seen.”

Mays told Scully, “Nobody talks about that.”

Scully replied, “I do!”

That was the start of Scully’s third year in the booth, age 24. There would be 64 more seasons with the Dodgers. That was the start of Mays’ second season in the big leagues, a month before he would turn 21. In ’51, he was the 1951 NL Rookie of the Year. Mays would only play 34 games in ’52 because he was drafted into the Korean War, which also took him out for the entire season. When he came back in 1954, he made 20 straight NL All Star teams.

For the record: Here’s the box score from that April 18, 1952 game, with a few corrections:

After the Dodgers swept a season-opening series in Boston against the Braves, and the Giants split two against Philadelphia in their opener at the Polo Grounds, the rivals met for the Dodgers’ home opener at Ebbets Field, a Friday afternoon game. This was their first meeting since the Bobby Thomson “Shot Heard ‘Around The World” at the Polo Grounds ended the Dodgers season on Oct. 3, 1951 and sent the Giants to the World Series in Mays’ rookie season.

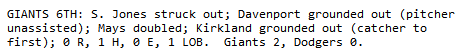

In the bottom of the seventh, the Giants were ahead 6-4, when Andy Pafko homered with two outs to make it 6-5. Gil Hodges singled and Carl Furillo walked to bring up Morgan, pinch hitting for pitcher Carl Erskine. Here’s how the description is written down for the record:

The Dodgers tied the game on Jackie Robinson’s solo homer with two out in the bottom of the eight and then won it in the bottom of the 12th inning on Pafko’s second homer of the game.

The game started with Clem Labine unable to get out of the first inning: He faced five batters, giving up four hits and then a walk to the No. 5 hitter, Mays, before Erskine came in, gave up a couple more hits, and Labine was charged with five earned runs. Which means the Giants squandered a 5-0 lead in the first inning. Erskine pitched seven innings of relief after Labine left. Billy Lowes then pitched five innings of scoreless relief to get the win nearly four hours after the first pitch. There were about 31,000 on hand to see it.

== July 19, 2024: Vin’s classic calls, as posted on Twitter, and stay until the last line when there is a closeup shot of Yankees manager Billy Martin:

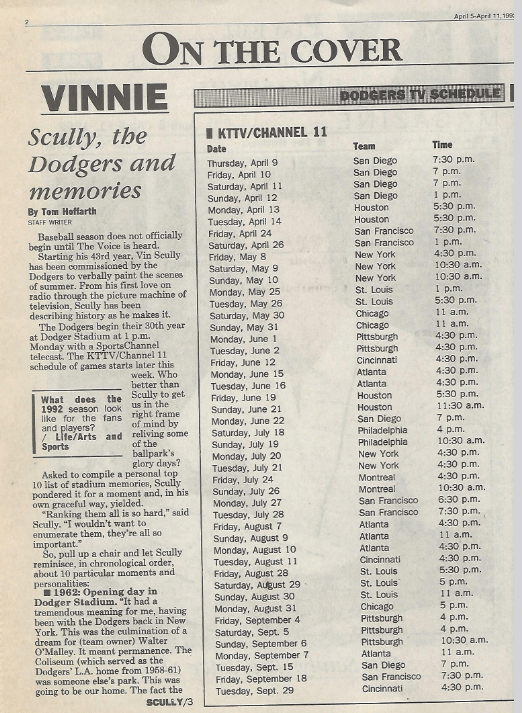

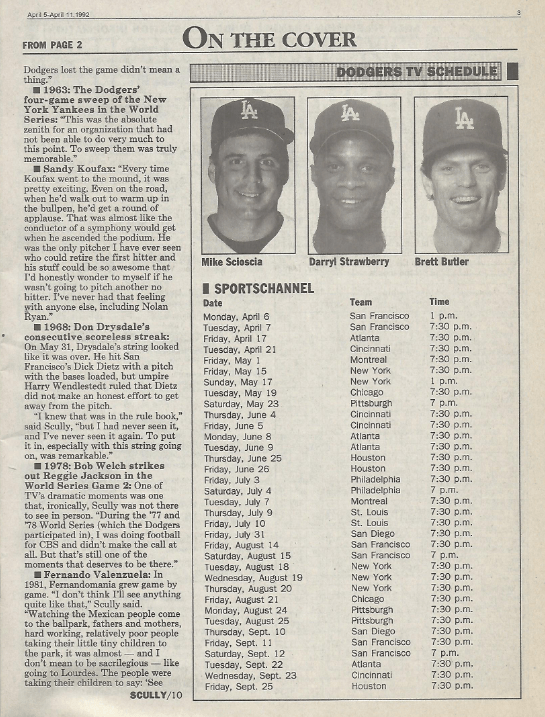

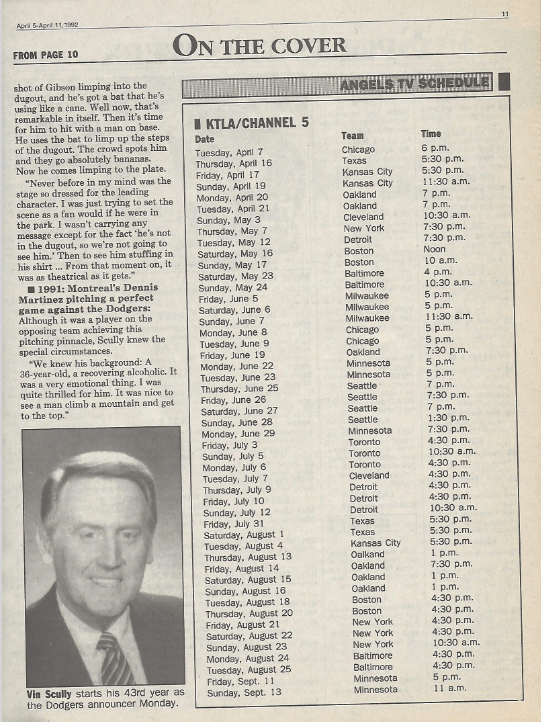

== Chapter 1 of “Perfect Eloquence” references a 1992 Daily Breeze TV Guide story assignment I had — my first sit-down with Vin Scully, at the Dodger Stadium press room. It was the start of his 43rd season. He would do 24 more.

Here is how the piece was displayed in print (there is nothing of it online), including the cove shot above that looks as if Vin is very confused about what’s happening with his scorecard:

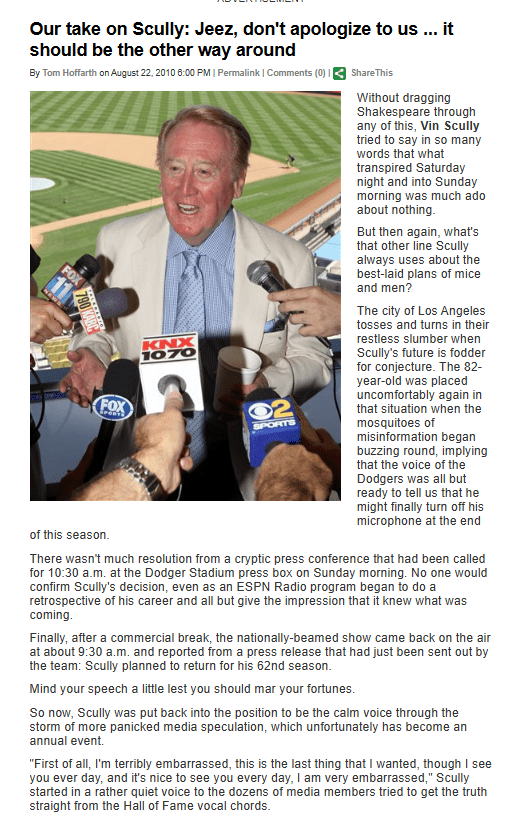

== August, 2010:

At a time when many wondered if Vin Scully would return to the booth, an impromptu press conference happened, the news came out he was staying, and relief was felt by many.

And, as it turned out, he stayed six more seasons.

Here is how the coverage went at that point in time:

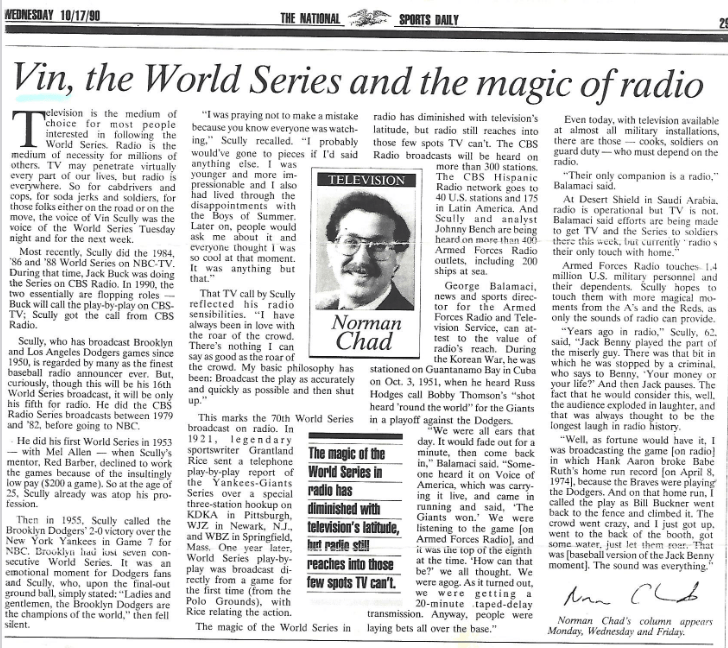

== October 17, 1990: From the short-lived publication The National, Norman Chad wrote this:

== 2024: “The Baseball Vault: Great Writing from the Pages of Sports Illustrated” is the latest example of a book publisher (Triumph) exploring the branding rights of a once iconic publication to squeeze more class and prose out of it. We reviewed that book last May.

Tom Verducci’s May 10, 2016 SI piece “The Voice of Baseball” is included in this latest volume. The story is available in the SIVault.com at this link. It includes that somewhat eerie cover illustration, as well as a nice video discussion Verducci had with Scully.

The last paragraphs of the story are saved for the end, as Verducci is asking Scully about the spring day in 2000 when he addressed the graduates of his alma mater of Fordham University.

“Oh, boy,” Scully says. “What an honor that was, you know?”

Scully spoke for 19 minutes that day. It was as far as he ever pushed himself “out ahead of the game.”

His words without baseball are even more beautiful and much more personal. His commencement address is as much the heart of eloquentia perfecta as its original definition in 1599.

The world “will try very hard to clutter your lives and minds,” Scully told them, but the way forward was to simplify and clarify.

“Leave some pauses and some gaps so that you can do something spontaneously rather than just being led by the arm.”

“Don’t let the winds blow your dreams away … or steal your faith in God.”

Drawing upon his own bouts of grief, “be a bobbed cork: When you are pushed down, bob up.”

“It is written that somewhere in every childhood a door will open, and there is a quick glimpse of the future. When my door opened, I saw a large radio on four legs in the living room of my parents’ home. Above all, don’t ever stop dreaming. Sometimes even your wildest dreams can come true.”

== In pulling together nine chapters of “Perfect Eloquence,” I tried to hone in on the most accurate descriptions of Scully’s attributes.

Chapter 6 became focused on kindness and friendship.

Or was it just about being nice?

In a story by The Atlantic’s Arthur C. Brooks in 2023, under the headline: “Make Yourself Happy: Be Kind“:

Kindness and niceness, though both excellent personal qualities, are not the same thing. The former is to be good to others; the latter is about being pleasant. They don’t even have to go together. Some say, for example, that New Yorkers are kind but not nice (“Your tire is flat, you moron—hand me your jack”), in contrast to Californians, who are nice but not kind (“Looks like you’ve got a flat tire there—have a good day!”).

Maybe Scully, the New York native and Californian transplant, could have melded the two together and made it work. And using neither of those sentences.

As for the concept of friendship, I found a piece in July 2023 from U.S. Catholic titled “The friendship recession is a problem for the common good.” It included these paragraphs that struck me as something Scully believed in:

For Aristotle, true friendship is a relationship of honesty, acceptance, and mutuality. In a relationship among equals, true friends love and accept one another for their own sake. It is not about competition or networking but rooted in virtue wherein we will the good for the other person, regardless of any benefit to us. Distinct from “imperfect friendships of pleasure or utility,” Aristotle believed true friendship was special and rare.

“Friendship is one of life’s gifts and a grace from God,” notes Pope Francis in Christus Vivit; “The experience of friendship teaches us to be open, understanding, and caring towards others, to come out of our own comfortable isolation and to share our lives with others.”

As we look around our society, the epidemic of loneliness seems deeply connected to increasing violence, intolerance, and an inability to dialogue.

True friendship is incarnate. Even those lived digitally must be embodied because we as people are embodied. Friendships involve something shared, but true friendship does not seek uniformity but the good of each other. It is not anonymous but personal. Isn’t this also what the synodal process is about? Perhaps in learning to discern together as the people of God, we might also learn how to be friends.

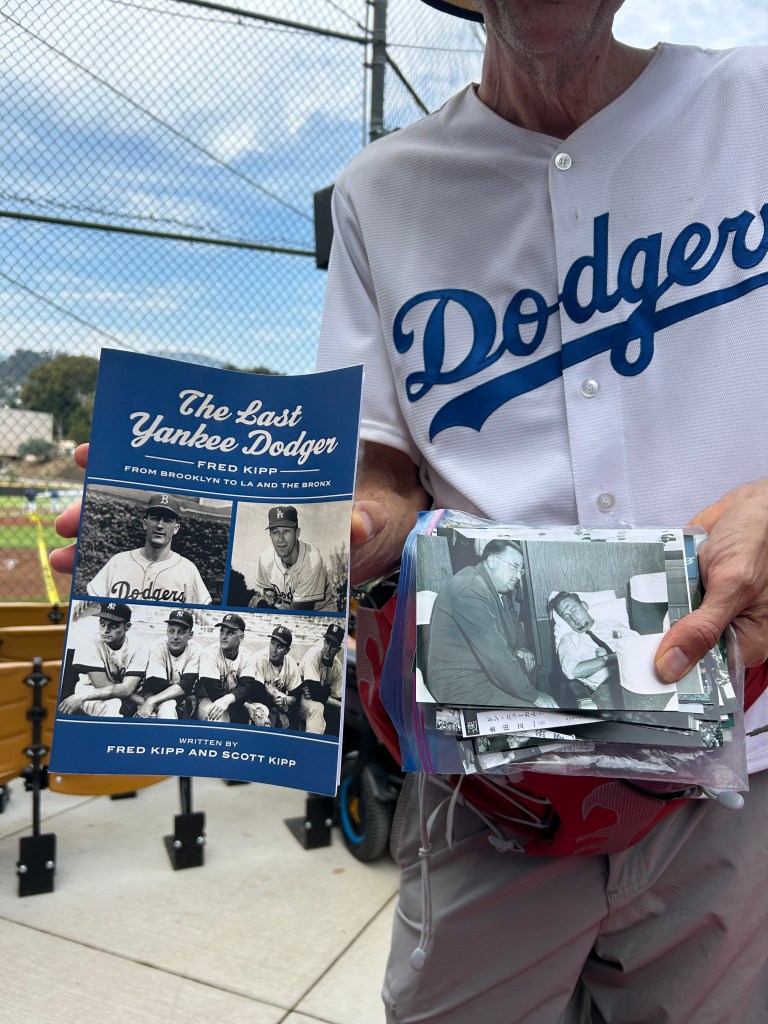

== 2018: “The Last Yankee Dodger: Fred Kipp from Brooklyn to LA and the Bronx” is a self-published book Kipp put together with his son, Scott, with the title focused on the fact Fred, who made it into 48 games and won six during his brief MLB pitching career, has become the last remaining Brooklyn Dodger to have also played with the rival New York Yankees.

According to Baseball Reference, Kipp started in the Dodgers organization as a 21 year-old out of Emporia State University in 1953 and was a 20-game winner at Triple-A Montreal in ’56 with 33 starts and 18 complete games. He made it into just one game during the team’s last season in Brooklyn — as a 25-year-old, making his MLB debut as he was rushed into a Sept. 10, 1957 game at Wrigley Field in the third inning, giving up four runs, including a homer to Ernie Banks, and making it through the seventh-inning stretch in an eventual 9-2 loss to the Cubs, as starter Sandy Koufax only faced six batters in the first, giving up three earned runs. Kipp moved with the team to Los Angeles and in his second Coliseum appearance got into the eighth inning of a start against St. Louis, picking up his first win in a 5-3 triumph (taken out after Stan Musial got his fourth hit in four at bats against him).

Kipp pitched in 42 games in ’58 and ’59 — his longest stint, 8 2/3 innings at San Francisco in an eventual 15-inning loss where Kipp gave up a sixth-inning home run to Willie Mays. Kipp was traded to the Yankees in the 1960 off season and pitched in four games, two at Yankee Stadium, including one in relief of Whitey Ford, and didn’t return to the big leagues after age 28, posting a 12-21 record in two more seasons at Triple-A as he was finished at age 30 in ’62. Kipp also had military service during the entire 1954 season at age 22.

As of July, 2024, when we met up with Scott Kipp at a Santa Barbara Foresters game, his father was 92 years old living in Kansas, three months shy of hitting 93.

Scott made sure we knew of his book, but also flashed of a photo his father had in his possession of Vin Scully. Look closer:

On page 123 of the book, Fred Kipp explained how the Dodgers’ flight after the 1956 World Series loss to the Yankees took them on an exhibition tour of Japan, and Scully was part of the party.

“Everybody was very exhausted and none more so than our announcer Vin Scully. Vin had been fighting bronchitis and had not slept much for a couple of nights. He’d just announced one of the most famous games of his illustrious career — Don Larsen’s perfect game. When Vin got on the plane, he fell into a deep sleep, and Walter O’Malley thought it would be funny to draw a unibrow across his forehead and a beard on his announcing prodigy. The result of O’Malley’s work is shown (in the photo). I knew this would be an unusual trip.” And that was just from New York to Los Angeles. Then it was to Honolulu. Then to Japan. A total of 29 hours in the air and 9,000-plus miles.

On the back of the book, Scully offers this blurb: “From Piqua, Kansas to Tokyo, Japan, with stops along the way in Ebbets Field, L.A. Coliseum and Yankee Stadium, Fred touched them all. You will be touched too when you read this book.”

== June 27, 2017:

A link to whatever the Southern California News Group might have of my stories that involve or include Vin Scully are here.

== June 27, 2000: Eight days after the Lakers won the NBA title and a 23-year-old Kobe Bryant, finishing his third season, is invited to throw out the first pitch at a Dodgers game. Vin Scully does the play by play:

Do you recognize this man? No, he’s not a very tall, slim right hander. He’s not somebody who is trying out for the Dodgers. That’s Kobe Bryant of the world champion Lakers. Threw out the first ball tonight, gets a hug from Dave Hansen and he got an ovation from this crowd.

Who has more murals of honor around Los Angeles these days, Bryant or Scully?

== There have been (so far) six official Vin Scully bobblehead nights at Dodger Stadium. The first was in August 30, 2012.

Why he did it finally? He told me in January of that year:

“Since I won’t be here for the 100th anniversary (of Dodger Stadium), I agreed to do the 50th. Otherwise, I would be open to questions as to way I didn’t do it. It’s far easier this way.”

Talk about foresight.

That ’12 bobblehead can fetch more than $100 these days on eBay. There are 3,000 limited edition versions that have audio sound and can go for more than $400 on eBay.

Additional bobblehead giveaways came out in 2013 (talking into a microphone) and another that season (holding binoculars and talking a mike), one in 2015 of him waving with the rainbow background (a spin off of the previous promotion for a 2014 talking microphone, and the last was near the end of 2016 (his retirement season).

In 2017, there was a commemorative microphone statue for his Ring of Honor night.

The most rare of the Dodgers’ Scully bobbleheads was a prototype produced for family and friends in 2002 that can go for as much as $20,000. Another odd one: A custom Dia De Los Muertos Sugar Skull White Bobblehead, for about $200.

There is also a limited bobblehead of Scully issued by his alma mater, Fordham University in 2024.

== Aug. 16, 2022: Robert Brennan did an essay for Angelus News on Scully’s impact on his life (which has been enhanced as being the brother of Bishop Robert Brennan) under the headline “A Hero Who Didn’t Let Us Down.” It included:

About eight years ago, I was planning a media event for a major nonprofit that required me to find someone of high standards to honor. Lots of names were bandied about when it dawned on me that Vin was the perfect honoree. I mentioned it to no one because I did not know Vin, knew of no reasonable way to contact him, and I did not want to overpromise and underdeliver.

I found two possible addresses and wrote letters to each of them, inviting Mr. Scully to our event. I realized it was a total long shot with little hope of success.

I know exactly where I was when my cellphone rang several weeks later. It was another holiday planning meeting. I did not recognize the number, and my usual modus operandi for unknown numbers was to let it go to voicemail. For a reason I cannot explain, I answered. On the other line was the most recognizable voice of my childhood asking if this was “Mr. Brennan.”

I immediately regressed to that 10-year-old boy, lying awake on a war surplus bunk bed on a hot summer night, listening on a small transistor radio to Vin Scully.